Seemingly overnight, the tech industry flipped from aggressive growth, hiring sprees, lavish perks and boundless opportunity to layoffs, hiring freezes and doing more with less.

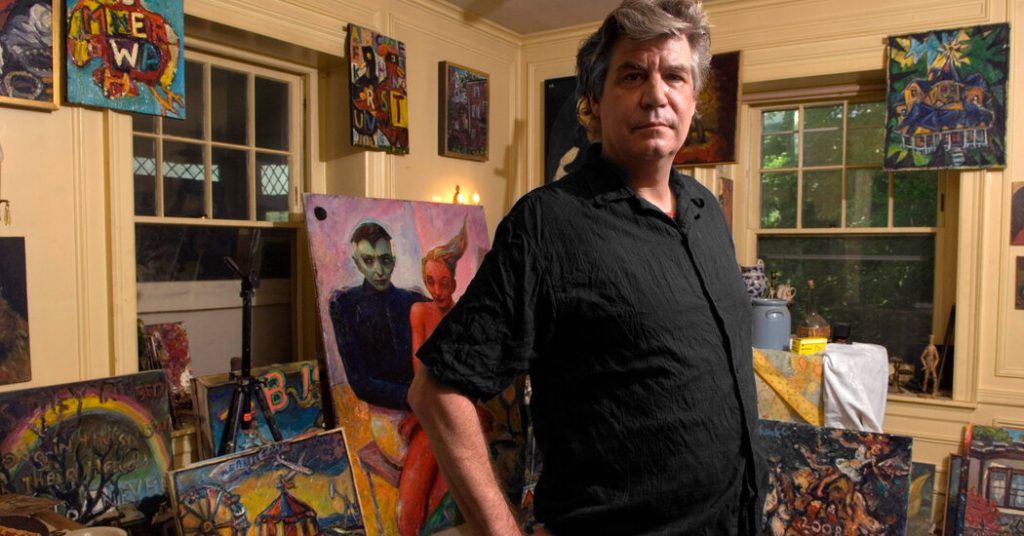

Nora Hamada, a 35-year-old who works with recruiters who hire employees for tech companies, is trying to be optimistic. But the change upended her online business, Recruit Rise, which teaches people how to become recruiters and helps them find jobs.

In June, after layoffs trickled through tech companies, Ms. Hamada stopped taking new customers and shifted her focus away from high-growth start-ups. “I had to do a 180,” she said. “It was an emotional roller coaster for sure.”

Throughout the tech industry, professional hirers — the frontline soldiers in a decade-long war for tech talent — are reeling from a drastic change of fortune.

For years during an extraordinary tech boom, recruiters were flush with work. As stock prices, valuations, salaries and growth soared, companies moved quickly to keep up with demand and beat competitors to the best talent. Amy Schultz, a recruiting lead at the design software start-up Canva, marveled on LinkedIn last year that there were more job postings for recruiters in tech — 364,970 — than for software engineers — 342,586.

But this year, amid economic uncertainty, tech companies dialed back. Oracle, Tesla and Netflix laid off staff, as did Peloton, Shopify and Redfin. Meta, Google, Microsoft and Intel made plans to slow hiring or freeze it. Coinbase and Twitter rescinded job offers. And more than 580 start-ups laid off nearly 77,000 workers, according to Layoffs.fyi, a crowdsourced site that tracks layoffs.

The pain was acute for recruiters. Robinhood, the stock trading app that was hiring so quickly last year that it acquired Binc, an 80-person recruiting firm, underwent two rounds of layoffs this year, cutting more than 1,000 employees.

Now some recruiters are adapting from blindly filling open jobs, known as a “butts in seats” strategy, to having “more formative” conversations with companies about their values. Others are cutting their rates as much as 30 percent or taking consulting jobs, internships or part-time roles. At some companies, recruiters are being asked to make sales calls to fill their time.

“Companies are being looked at pretty dramatically differently in the investor market or public market, and now they have to pretty quickly adapt,” said Nate Smith, chief executive of Lever, a provider of recruiting software.

It is a confusing time for the job market. The unemployment rate remains low, and employees who outlasted the “Great Resignation” of the millions who quit their jobs during the pandemic became accustomed to demanding more flexibility around their schedules and remote working.

Nora Hamada’s program for training recruiters, Recruit Rise, grew quickly after she started it last summer.Credit…Leah Nash for The New York Times

But companies are using layoffs and the specter of a recession to assert more control. Mark Zuckerberg, chief executive of Meta, said he was fine with employees’ “self-selection” out of the company as he set a new, relentless pace of work. Some companies have asked employees to move to a headquarters city or leave, which observers say is an indirect way to trim head count without doing layoffs.

Plenty of tech companies are still hiring. Many of them expect growth to bounce back, as it did for the tech industry a few months after the initial shock of the pandemic in 2020. But companies are also under pressure to turn a profit, and some are struggling to raise money. So even the best-performing firms are being more careful and taking longer to make offers. For now, recruiting is no longer a top priority.

Recruiters know the industry is cyclical, said Bryce Rattner Keithley, founder of Great Team Partners, a talent advisory firm in the San Francisco Bay Area. There’s an expression about gumdrops — or “nice to have” hires — versus painkillers, who are employees that solve an acute problem, she said.

“A lot of the gumdrops — that’s where you’re going to see impact,” she said. “You can’t buy as many toys or shiny things.”

Ms. Hamada started Recruit Rise in July last year, when recruiting firms were so overbooked that companies had to call in favors for the privilege of their business. Her company aimed to help meet that demand by offering people — typically midcareer professionals — a nine-week training course in recruiting for technical roles.

The program grew quickly, forging relationships with prominent venture capital firms and Y Combinator’s Continuity Fund, which helped funnel students from Ms. Hamada’s program into recruiting jobs at high-growth tech start-ups.

In May, emails from companies wanting to hire her students started tapering off. The venture firms she worked with began publishing doom-and-gloom blog posts about cutbacks. Then the layoffs started.

Ms. Hamada stopped offering new classes to focus on helping existing students find jobs. She scrambled to contact companies outside the tech industry that were hiring tech roles — like banks or retailers — as well as software development agencies and consulting groups.

“It was a scary period,” she said.

For Jordana Stein, the shift happened on May 19. Her start-up, Enrich, hosts recurring discussion groups for professionals. In recent years, the most popular one was focused on “winning the talent wars” by hiring quickly. Enrich’s virtual events typically filled up with a wait list. But that day, three people showed up, and they didn’t talk about hiring — they talked about layoffs.

“All of a sudden, the needs changed,” Ms. Stein, 39, said. Enrich, based in San Francisco, created a new discussion group focused on employee morale during a downturn.

Pitch, a software start-up based in Berlin, froze hiring for new roles in the spring. The company’s four recruiters suddenly had little to do, so Pitch directed them to take rotations on other teams, including sales and research.

By keeping the recruiters on staff, Pitch will be ready to start growing quickly again if the market rebounds, said Nicholas Mills, the start-up’s president.

“Recruiters have a lot of transferable skills,” he said.

Lucille Lam, 38, has been a recruiter her entire career. But after her employer, the crypto security start-up Immunefi, slowed its recruiting efforts in the spring, she switched to work in human resources. Instead of managing job listings and sourcing recruits, she began setting up performance review systems and “accountability frameworks” for Immunefi’s employees.

“My job morphed heavily,” she said.

Ms. Lam said she appreciated the chance to learn new skills. “Now I understand how to do terminations,” she said. “In a market where nobody’s hiring, I’ll still have a valuable skill set.”

Matt Turnbull, a co-founder of Turnbull Agency, said at least 15 recruiters had asked him for work in recent months because their networks had dried up. Some offered to charge 10 percent to 30 percent below their normal rates — something he had never seen since starting his agency, which operates from Los Angeles and France, seven years ago.

“Many recruiters are desperate now,” he said.

Those who are still working have it harder than before. Job candidates often get stuck in holding patterns with companies that have frozen budgets. Others see their offers suddenly rescinded, leading to difficult conversations.

“I have to try to be as honest as possible without discouraging them,” Mr. Turnbull said. “That doesn’t make not being not wanted any easier.”

At Recruit Rise, Ms. Hamada restarted classes to train recruiters in late August. Steering her students away from start-ups funded by venture capital has shown promise, even if some of them have started with internships or part-time work instead of a full-time gig.

Ms. Hamada is hopeful about the new direction, but less so about the tech companies propped by venture capital funding. “They’re not looking that stable right now,” she said.