Who Owns the ‘Victorious Youth’?

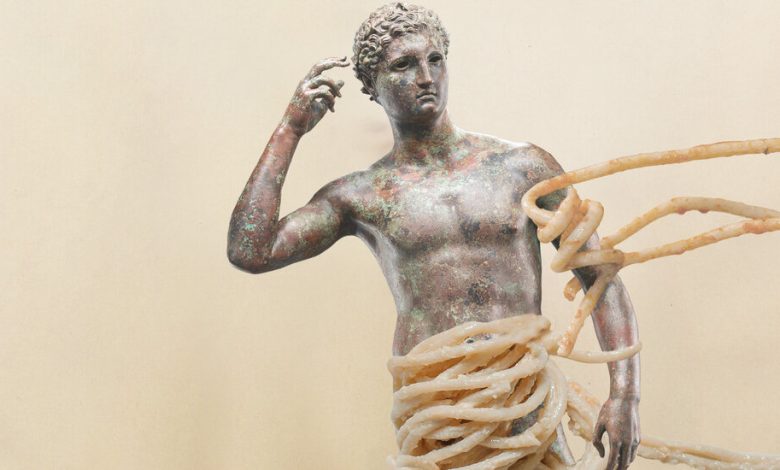

In the summer of 1964, Italian fishermen recovered an antique bronze statue from the seabed off Italy’s Adriatic coast. They landed it in the small port of Fano, where it disappeared for almost a decade; apparently it spent some time in a priest’s bathtub and a cabbage patch. It reappeared in the gallery of a Munich art dealer who dated it to around 400 B.C. and claimed that it was the work of Lysippos, an Athenian sculptor. The Getty Foundation bought it in 1977 for almost $4 million and put it on display as the “Victorious Youth” at the Getty Villa, where it still is.

Though maybe not for much longer. In 2018 Italy’s highest court declared the statue the property of Italy — while conceding that it might have been discovered in international waters and that the sculptor was probably Greek.

Some of the reasoning was technical: The statue had been landed at an Italian port by an Italian-flagged vessel and had remained on Italian soil for several years. Some arguments depended on historical interpretation: When the statue was created, the judge said, “the artist had most probably visited Rome and Taranto.” The judge added, “At the relevant time, Greece and Rome had enjoyed good relations, and thereafter, Roman civilization developed as a continuation of Hellenic civilization.” These considerations were, in the judge’s view, sufficient to establish a “significant connection” with Italy, a state that came into existence in 1861. In May, the European Court of Human Rights upheld Italy’s right to seize the statue.

This is a time of reckoning for museums. There is widespread agreement, even in museums, that questionable pieces in collections should be returned. But returned to whom? If a statue cast in Greece 2,000 years ago is discovered off the coast of Italy, is it part of the heritage of modern Italy? The Italian courts seem to think so. If a statue cast in Rome 2,000 years ago is discovered in Greece, Cyprus or Turkey, would it belong to one of those states, or would Italians have a claim over Roman antiquities on the ground that they share a culture — whatever that may mean — with ancient Romans? Is the modern Italian Republic the heir to the multiethnic Roman Empire, which spanned most of Europe, the Near East and parts of North Africa for more than four centuries?

These are hard questions that may not have satisfactory answers. When an item is hundreds of years old, museums cannot simply hand it back to a person it once belonged to, and it is not usually a straightforward matter to identify the original owners or their descendants. The default response is to send the object to the rulers of the modern nation within whose boundaries it was probably first found. That can lead to incongruities.

Consider a recent case that came out of the Manhattan district attorney’s office. Matthew Bogdanos, the assistant district attorney who heads that department’s Antiquities Trafficking Unit, presented to the Chinese Consulate in New York 38 miscellaneous East Asian antiquities that his office had confiscated. Among them were what Kate Fitz Gibbon, the executive director of the Committee for Cultural Policy, a U.S. think tank, described to me in an email as “a grab bag” of Tibetan Buddhist objects, some of them “likely copies.”