Ever since the German Parliament building reopened in Berlin in 1999, its second-largest meeting room has been occupied by what had often been Germany’s second-largest party, the Social Democrats.

Even the room’s name, the Otto Wels Hall, bears the party’s imprint: Wels led the Social Democrats from 1919 until the Nazis drove him to exile.

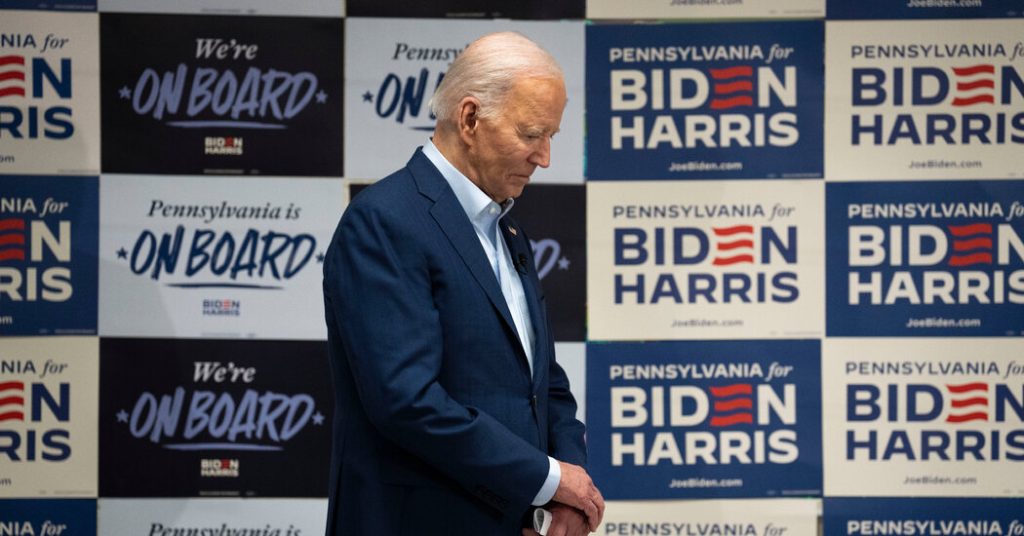

Now, following their disastrous performance in February’s federal elections, the Social Democrats may lose the room to the far-right Alternative for Germany, or AfD, which came in second and insists that, by the rules of the Parliament, it should get the room instead.

The fight over the Wels Hall is just one in a series of challenges facing the Social Democrats and their senior partners in the incoming governing coalition, the center-right Christian Democrats, as they prepare to confront the AfD.

Most important, they are considering how to deal with a party that is both politically toxic and yet powerful enough to undermine the coalition’s agenda.

Heightening the tensions was a decision on Friday by Germany’s domestic intelligence service declaring the AfD an extremist organization.